Health experts are questioning the Environmental Protection Agency and Michigan state officials for their decades-long delays in cleanup of a Superfund site that is killing songbirds in yards, possibly leaving people at risk, too.

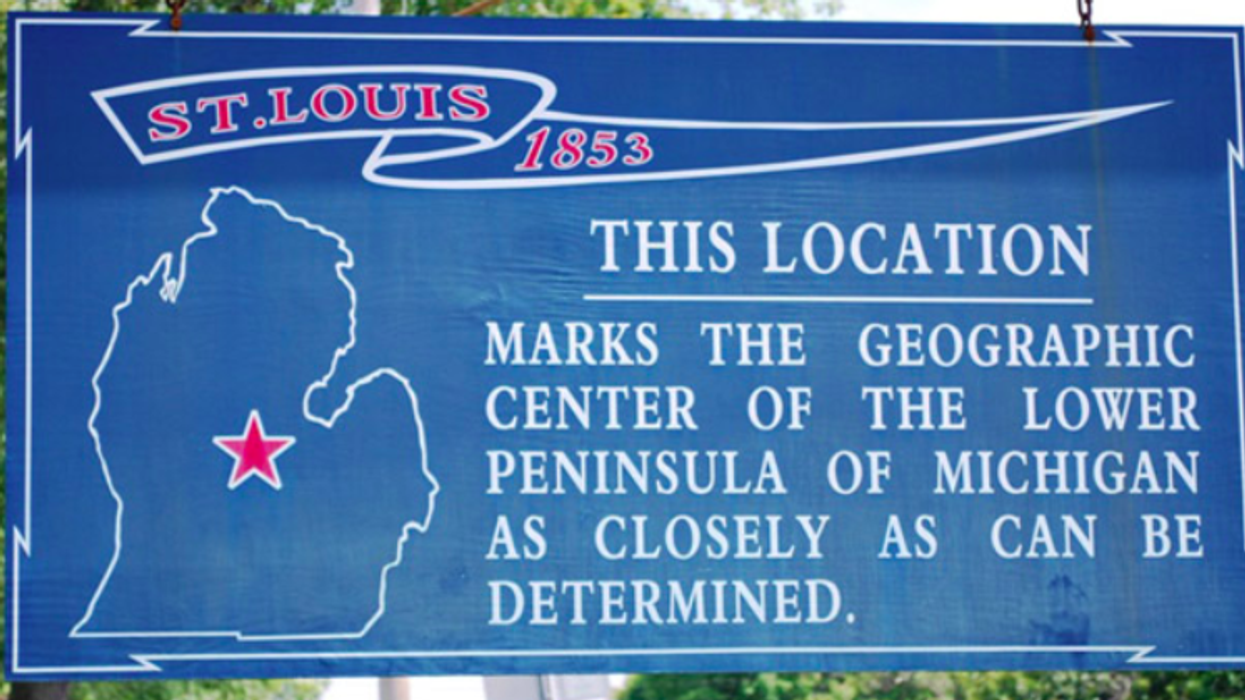

After years of complaints from residents, researchers recently reported that robins and other birds are dropping dead from DDT poisoning in the mid-Michigan town of St. Louis, which was contaminated by an old chemical plant.

"The more we know about DDT the more dangerous we find out it is for wildlife, yes, but humans, too," said Dr. David Carpenter, director of the University at Albany - State University of New York's School of Public Health and an expert in Superfund cleanups.

Velsicol Chemical Corp., formerly Michigan Chemical, manufactured pesticides at the plant until 1963. DDT, known for accumulating in food webs and persisting for decades in soil and river sediment, was banned in the United States in 1972.

The dead robins and other songbirds tested last month at Michigan State University had some of the highest levels of DDT ever recorded in wild birds. They were contaminated by eating worms in the neighborhood's soil.

The EPA has been in control of the Superfund site since 1982, and the residents and songbirds have been living with the highly-tainted soil in their yards for decades. This summer, EPA contractors are excavating contaminated soil from 59 yards in the town of 7,000 people. Another 37 yards will be cleaned up next year.

EPA and state officials are not conducting any testing to determine how highly exposed the residents are, or whether they are experiencing any health effects.

Carpenter said research elsewhere has linked DDT exposure to effects on fertility, immunity, hormones and brain development. Fetuses are particularly at risk. It also may induce asthma.

"Let's say your backyard has DDT in it. If wind blows, and kicks up dust, you might [be exposed to] DDT. The sun shines, water evaporates, you might get a little DDT," Carpenter said. "And who knows what other chemical exposure they're getting from the site."

Michele Marcus, an Emory University epidemiologist, said she and her team of health experts heard "shocking stories" when they visited the neighborhood near the dismantled chemical plant last December.

"We heard from several people in the neighborhood that back in the day [decades ago] on several occasions alarms would go off and the neighborhood would be covered in white powder," Marcus said. "It would take the paint off of people's cars. Imagine what it was doing to people."

When asked why it took three decades to address contamination in people's yards next to the plant, Thomas Alcamo, remedial project manager for the Superfund site, said "hindsight is 20-20." He said there were some "obvious problems" with the initial cleanup but he maintained it was "not an oversight."

"This was just a natural progression of the Superfund. It's just a continual investigation of the plant site itself," Alcamo said. "Then we looked at the [Pine] river and focused efforts there. Then the state looked at residential areas."

The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality started sampling some yards in a nine-block area near the plant in 2006, after complaints from residents. Orange fences were installed around heavily contaminated areas. The EPA cleaned up those yards in 2012, Alcamo said. Further sampling, however, found that nearly the entire neighborhood needs cleanup so more excavations began this summer.

Jonathan Chevrier, an epidemiologist at McGill University, said research suggests that fetuses and young children are most vulnerable to DDT. The major worry is brain development in the womb, he said. "Research shows those with prenatal exposure scored lower on neurodevelopmental scales," which can indicate lower IQs, he said.

There also is evidence that DDT is linked to low birth weights. In addition, a study last month found female mice exposed as a fetus were more likely to have diabetes and obesity later in life.

"The way it kills insects is by affecting the nervous system. It induces a rapid firing of neurons, exhausts them, and then the insect is killed," Chevrier said. "It's very plausible that it would attack humans' nervous systems in the same way." DDT also may disrupt thyroid hormones, which are critical for brain development, he said.

Nevertheless, EPA officials said St. Louis residents are not in danger. Alcamo said the levels in the soil are not high enough to pose an immediate risk to people.

"This [cleanup] is all for long-term risk so there's no one that needs to leave during cleanup activities," he said.

The EPA has not issued recommendations on gardening or other activities while the yards are cleaned up, other than keeping people away from the removed dirt. The agency is monitoring air and controlling dust, Alcamo said. "As long as they wash vegetables," they should be fine because DDT doesn't uptake into plants, he said.

However studies have found that some plants can take up DDT, including pumpkin and zucchini and some corn.

Health experts disputed Alcamo's contention that the DDT levels are not high enough to pose a risk to people. There is no such thing as a level of DDT that "we don't need to worry about," Carpenter said.

"It doesn't seem like there's a clear health threshold," Chevrier added. "That doesn't mean there isn't one, but, if there is, scientists haven't found it."

Velsicol is infamous for one of the worst chemical disasters in U.S. history: In 1973 its flame retardant compound – polybrominated biphenyls, or PBBs – was mixed up with a cattle feed supplement, which led to widespread contamination in Michigan.

Marcus and her colleagues are studying people exposed during the PBB mix-up. They also have launched a new study to examine the levels of PBB, DDT and other chemicals in former Velsicol workers and their families.

Some of the chemical workers in Marcus' study live adjacent to the plant, but the study does not cover the entire contaminated neighborhood.

Alcamo said community health studies are "outside the scope" of what the EPA does.

Most of the contamination is in the top six inches of the soil, probably from the chemicals drifting over from the plant, but some yards have DDT as deep as four feet, according to an EPA report from April.

All 59 houses tested had at least one soil sample that contained more than 4.1 parts per million of DDT that the EPA set as a cleanup standard. Two-thirds of the yards had at least one sample with more than double the 4.1 parts per million guideline.

The EPA uses a DDT cleanup standard of 5 parts per million based on studies to protect wildlife health, Alcamo said.

"We are using an excavation level of 4.1 ppm DDT to ensure that we are 95 percent confident that we are meeting the 5 ppm number," he said.

Michigan's cleanup criteria, based on protecting people from exposure, is 57 ppm for DDT. One home had levels more than twice that amount –140 parts per million in the top six inches of soil.

Alcamo said the EPA is now over-excavating many yards to be certain of cleanup. Contractors will remove about 30,000 tons of contaminated soil this summer.

Alcamo said the EPA has made "great progress," including a Pine River cleanup. There's been a "98 percent reduction in fish tissue concentrations of DDT," he said.

In addition, the EPA is providing 90 percent of the funding to overhaul St. Louis' drinking water supply because low levels of a DDT byproduct, pCBSA, have been found in the city's water system.

But Gary Smith, a lifelong resident of St. Louis, said the EPA failed St. Louis on the first round of cleanup, and it cannot happen again.

"We just want the doggone neighborhood cleaned up so we can put an end to this," said Smith, 63, who is treasurer of the Pine River Superfund Citizen Task Force. "We don't want to be called a toxic town. We want people to say 'hey, they cleaned it up.'

"Let's go the extra mile and not have this be an embarrassment for the EPA again," he said. "'We have no money' may be true, but it's a poor excuse."

Carpenter said it's unfortunate that people were probably exposed to DDT for many years. "The EPA is simply overwhelmed with hazardous sites," Carpenter said.