While tainted water and flaking paint remain a problem nationwide, decreasing levels of toxic lead in dirt is an important factor in reducing kids' exposure, according to a new study out of New Orleans.

Lead built up in soils largely due to lead-based paint and tetraethyl lead, which used to be added to gasoline to prevent engine knock. However, the metal—which causes irreversible impacts on brain development, leading to behavior or learning problems, decreased IQ, hyperactivity, and is also linked to delayed growth, hearing problems, anemia and kidney disease—has been decreasing as these sources have been phased out.

The new study, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggests that prevention strategies should go beyond lead-paint remediation and removal in homes.

"Lead dust is invisible and it's tragic that lead-contaminated outdoor areas are unwittingly provided for children as places to play," said lead study author Howard Mielke, a pharmacology research professor at Tulane University School of Medicine, in a statement. "Young children are extremely vulnerable to lead poisoning because of their normal crawling, hand-to-mouth, exploratory behavior."

Mielke and colleagues started tracking lead in New Orleans soil in 2001 and collected about 5,500 samples near homes, along streets and in parks. Then 16 years later they sampled again: those later samples showed a 44 percent decrease in soil lead.

This mirrored the lead in children's blood: there was a 64 percent decrease in New Orleans children's blood lead levels from a round of testing in 2000-2005 to the 2011-2016 time-frame.

The study builds upon earlier research by Mielke published in 2016 in which they looked at fewer census tracts but also found corresponding reductions in soil lead and children's blood levels.Lead hazard prevention programs often focus entirely on removing lead-based paint in older homes—US guidelines for lead dust say "soil sampling is necessary in a lead hazard screen only if there are paint chips on the ground."

Mielke and colleagues said the new study should foster more wide-ranging cleanup and prevention strategies to keep children safe. "Primary prevention requires determining all sources and reducing or eliminating environmental lead wherever it is found before, not after, children are exposed," they wrote.

Many city officials feared a spike in lead exposure after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. However, Mielke and others believe soil and blood levels dropped instead because the floodwaters brought new soil into the city that laid on top of polluted soil, and post-flood restoration and renovation in homes and yards further the lead cleanup.

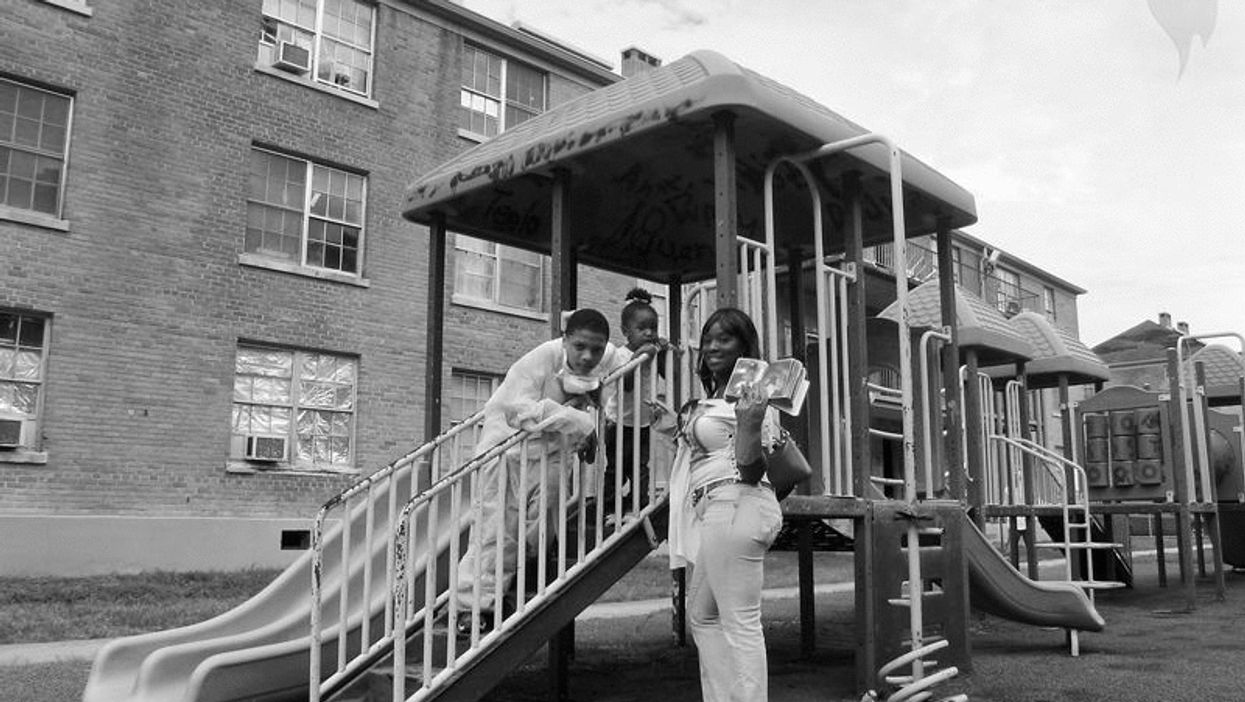

Racial disparities remain

Even though levels decreased across the city, black children in New Orleans were still three times more likely to have higher blood lead levels than white children. The researchers said it is partially due to black families' proximity to roads and heavy industry and older housing.

"While the metabolism of the city could theoretically affect all residents equally, in reality social formations produce inequitable outcomes in which vulnerable populations tend to bear greater burdens of contaminant exposure," Mielke said.

Researchers also pointed out that, while the reductions in New Orleans soil are positive, there is no safe level of lead for kids' developing brains.

"The current topsoil data also show that many inner-city communities remain too lead-contaminated to appropriately support children's health and welfare trajectory into adulthood," they wrote.