INDIANAPOLIS—Jeff Stant was nervous. He passed easily through the undergrowth and spring pools of an unlikely old growth forest standing five miles from downtown Indianapolis, but he was looking out for contractors working for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

“I’m waiting for some people to show up and tell us to leave,” said Stant, executive director of the Indiana Forest Alliance.

Over the background noise of chickadees, crunching leaves, humming traffic and a leaf blower clearing the shoulder along 42nd Street, Stant spent that morning in early March extolling the virtues of the Crown Hill North Woods — a 15-acre pre-settlement relict of the flatwood swamp forest that once covered much of the state. His organization spent the past year working to spare the woods from a VA plan to clear part of the land for a National Cemetery.

“You can count the number of forests you have like this basically on two hands in the northern two-thirds of this state,” Stant said.

“You can count the number of forests you have like this basically on two hands in the northern two-thirds of this state." -Jeff Stant, Indiana Forest Alliance The VA bought the North Woods in 2015 from the city’s historic Crown Hill Cemetery, which had for decades left the forest alone while letting visitors walk among the oak, hickory, tulip poplar and beech trees, some of which are estimated to be 300 to 500 years old. That gave residents of the Crown Hill Neighborhood access to “a true high quality remnant of Indiana's pre-settlement forest,” according to a 2008 assessment from the Indiana Department of Natural Resources. “In the context of Marion County, it is a very rare and special resource.”

The definition of “old growth” remains nebulous, even among scientists and foresters, but one thing is certain: Only a fraction of U.S. old growth forests still stand, and they’re especially rare in and around cities. Urban old growth forests near population centers can show off a region’s natural heritage and provide ecological services to more people than their rural kin, but they’re also under more environmental pressure.

Stewards of these old woods are working at timescales beyond the human lifespan to manage threats from human traffic and invasive species to — in the case of the Crown Hill North Woods — potential destruction.

Less pollution and a peek in the past

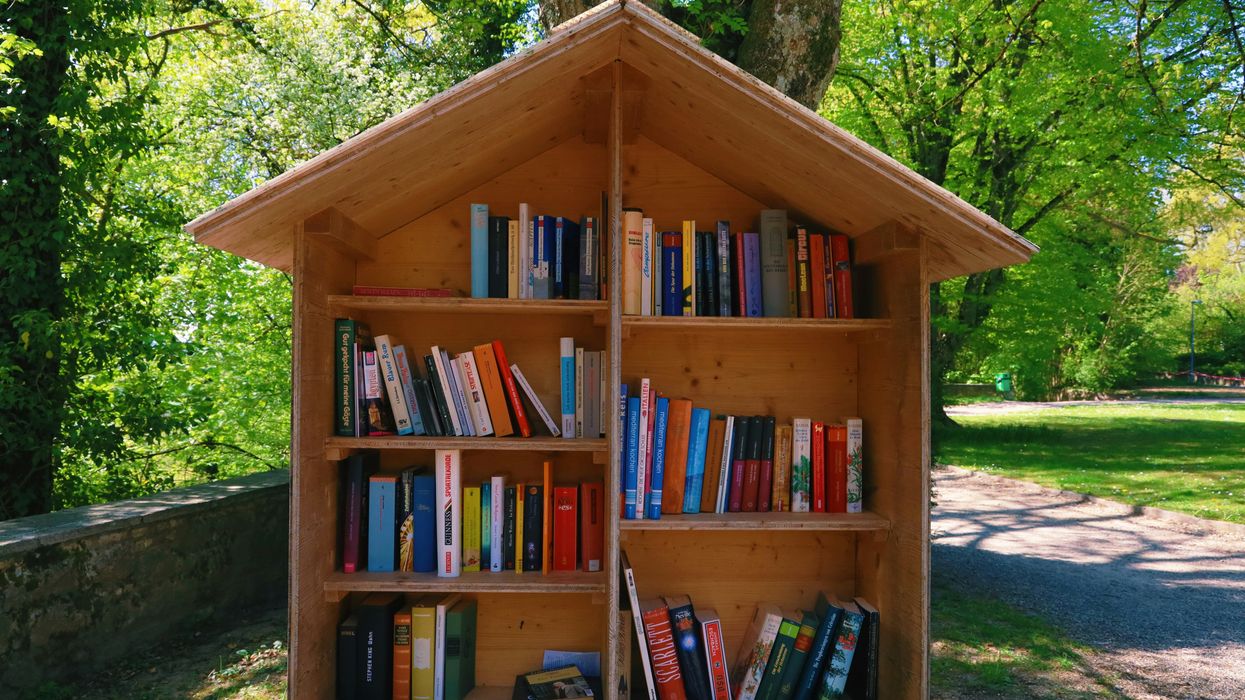

Forest Park in Portland, Ore. (Credit: Jeremy McWilliams/flickr)

The stakes are much lower 1,800 miles away in a 30-acre old-growth stand of towering Douglas firs and oaks a short drive from downtown Portland, Oregon. The Forest Park Conservancy owns this property and another 9 acres of adjacent younger edge habitat, together dubbed the Ancient Forest Preserve.

“We’ve been sitting on it for 20 years, haven’t really done anything to it, which is great,” said Renee Meyers, the conservancy’s executive director, from the preserve’s lone trail carved into a fern- and moss-covered hillside. “The idea behind buying it was we just want to protect it.”

Visitors to the ancient preserve go there because it has a “different feel, it feels peaceful and calm,” Meyers said, while pointing out a 450-year old Douglas fir tree. “That one, you hug it and it just kind of hums.”

Related: Trees, science and the goodness of green space Meyers is on to something: Research has linked forest visits to health benefits such as stress reduction and stronger immune systems. Urban forests also mitigate the urban heat island effect and filter pollutants from air and water, and are considered crucial in helping cities both tackle and adapt to climate change.

Green spaces also appear to reduce some crime rates, according to a U.S. Forest Service study. That’s especially relevant in the Crown Hill Neighborhood, where community leaders in September celebrated 300 days without a homicide after a concerted effort to reduce violent crime, only to see the streak end at 369 in November.

Urban old growth forests like the ancient preserve and the North Woods tend to harbor greater ecological complexity and biological diversity while giving city-dwellers a glimpse of what their states looked like before white colonists began cutting forests centuries ago. Even city forests that were logged at some point could fall under the definition of “urban old growth forest” used by experts like Robert Loeb, professor of biology and forestry at the Pennsylvania State University DuBois Campus.

If the forest is at least as old as the last round of widespread forest destruction that tends to precede city-founding, it counts.

While defining an urban old growth forest may vary depending on location, the loss is ubiquitous. Researchers estimate that tree cover in U.S. urban areas is declining at a rate of roughly 19,000 acres a year — or 4 million trees.

Tackling invasives, maintaining a treasure

Popular city trees have long fell victim to alien invaders. The American elm, once a mainstay in U.S. cities, was decimated by Dutch elm disease, which was spread by elm bark beetles from Europe. By the 1960s, millions of trees were taken out of cities and suburbs and were often replaced by ash, which have their own imported nemesis, the emerald ash borer. The borer killed millions of ash trees in Metro Detroit, and tens of millions in other Midwestern and southern states.

Indiana Forest Alliance

While bugs can wreak havoc, urban foresters tend to start management with removing non-native plants, Loeb said, as many invasive species are much better adapted to urban environments than native species.

“Displacing these is tough, and you really do need human intervention,” he said.

“For an urban old growth forest, the community can be its most important asset or its most bedeviling problem.”-Robert Loeb, Pennsylvania State University Invasives are the biggest problem in Portland’s Forest Park, the Forest Park Conservancy’s namesake that covers 5,200 city-owned acres on the Tualatin Mountains a few miles south of the old growth preserve. A $10 million, 15-year removal plan is underway there, with ten projects targeting the English and Irish ivy seen covering the trees and hillsides along highways in and out of the city. But those species haven’t shown up in the old growth forest yet.

“We have some invasive species on the outside edge habitat, but it seems that there’s this natural barrier to them going into the old growth,” she said. ”It’s definitely more resilient.”

Another rule of thumb for protecting urban old-growth forests from overuse, Loeb said, is to build trails and signs to keep visitors from trampling the forest floor helter-skelter. That gives seedlings a better chance to take hold and renew the forest canopy.

But the most important work, more so than any particular invasive removal or trail building project, is building sustained leadership and community engagement, said Loeb, who literally wrote the book on urban old growth forests.

“For an urban old growth forest, the community can be its most important asset or its most bedeviling problem,” he said. “If people come to realize what the treasure is that they have in these forests, then the behaviors of the people around the forest help the forest. Where no one cares, it really becomes quite a problem.”

Loeb credits his career path to his childhood years spent at the New York Botanical Gardens in the Bronx, especially an early job mapping their hemlock forest that he said is likely one of the premier urban old growth forests in the nation.

But he lived next door to Seton Falls Park, where people would dump and burn used cars in a forest dating back to the American Revolution. That turned him from a “cold scientist” to an advocate who worked with the community to understand the value of the forest and with the parks department to build barriers against dumping, he said.

Long-term leadership and dedication is vital to protecting urban old-growth forests, where the complexity of a centuries-old ecosystem can turn even an obvious preservation strategy like invasive removal into an intractable problem.

Loeb said the Saddler’s Woods Conservation Association in New Jersey, for example, is as devoted to removing invasives as any group he’s worked with. But in some cases, they’d finish off one non-native species only to watch two more move in.

“You really need groups that have had the bug bite them to continue to look at these forests and continue to improve them,” he said. “You really need fresh ideas and fresh dedication to helping these forests in the long term. Even longer than my life. Far longer than my life.”

That puts a premium on outreach to cultivate the next generation of advocates, volunteers and donors.

The Forest Park Conservancy struggled with how much to open its old growth preserve to the public, Meyers said, but decided that the best recruiting tool is the forest itself. Last summer they built a new trail to accommodate the off-road cyclists that are banned from forests closer to the city. An empty frame of fresh lumber that will house an interpretive kiosk on the importance of old growth marks the trailhead.

“For us, it seems like a shame not to have people be able to appreciate it so they understand it and want to protect it,” Meyers said.

Credit: Indiana Forest Alliance

Appreciate the wild

Back in Indiana, people both understand and care about the North Woods. After some brush clearing started in early March a group of citizens, including veterans, organized a protest, putting out a press release and occupying the access site.

Within a few hours, the VA called off construction.

It isn’t clear what brought on the last-minute change of heart, and the agency didn’t respond to questions about their plans moving forward. Ronald Walters, the interim undersecretary for memorial affairs, released a statement that said any alternative sites of a similar size that are suitable for cemetery development and large funeral processions would get a “good hard look.” The VA will also seek reimbursement for its expenses on the Crown Hill site.

While the stop-work order felt like a victory for the protestors, Stant won’t be at ease until the National Cemetery Administration picks another site. He says he knows they’ve gotten proposals, but would like to hear more from the VA.

“We’re pleased that they’re looking at alternatives,” Stant said in an interview after the order. “But we’re very anxious that they have not actually called us.”

Whether the North Woods ultimately survive or not, Stant said, he thinks the controversy is having the benefit of waking people up to the value of their natural heritage, something they lose sight of when they buy into Indiana’s national reputation as flyover country.

“I hope we save these woods," he said. “But if we don’t, at least use them as a springboard to eventually bring change to Indiana, a greater public acknowledgement and appreciation of wild nature.”